A Fly and a Whale, 2019, Oil, acrylic, and ink on panel,

46 x 32 in.

Corruption of the Flesh (After Jan van Huysum), 2019,

Graphite on paper, 6.5 x 7 in.

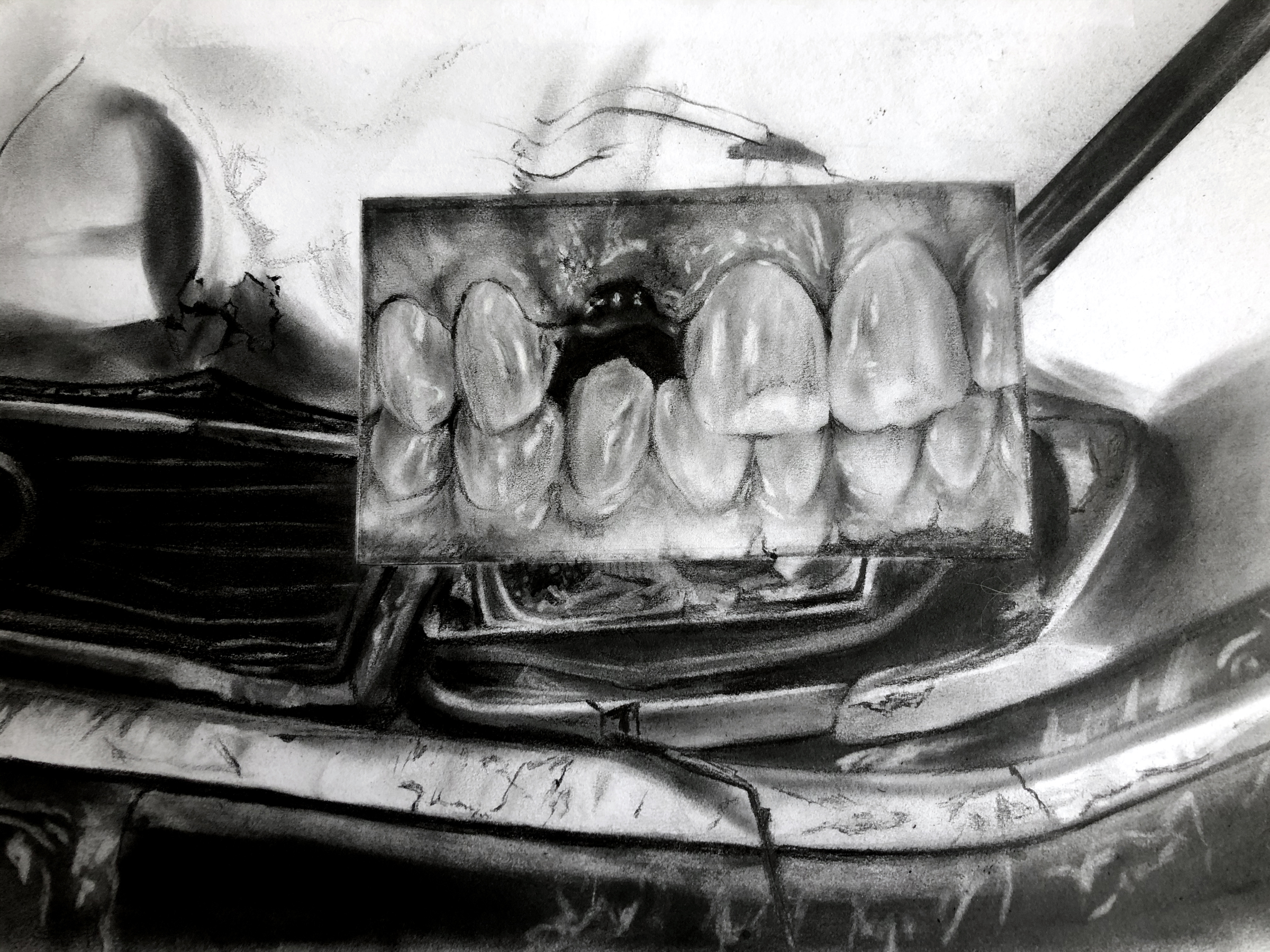

Crash, 2020, Graphite on paper, 9 x 12 in.

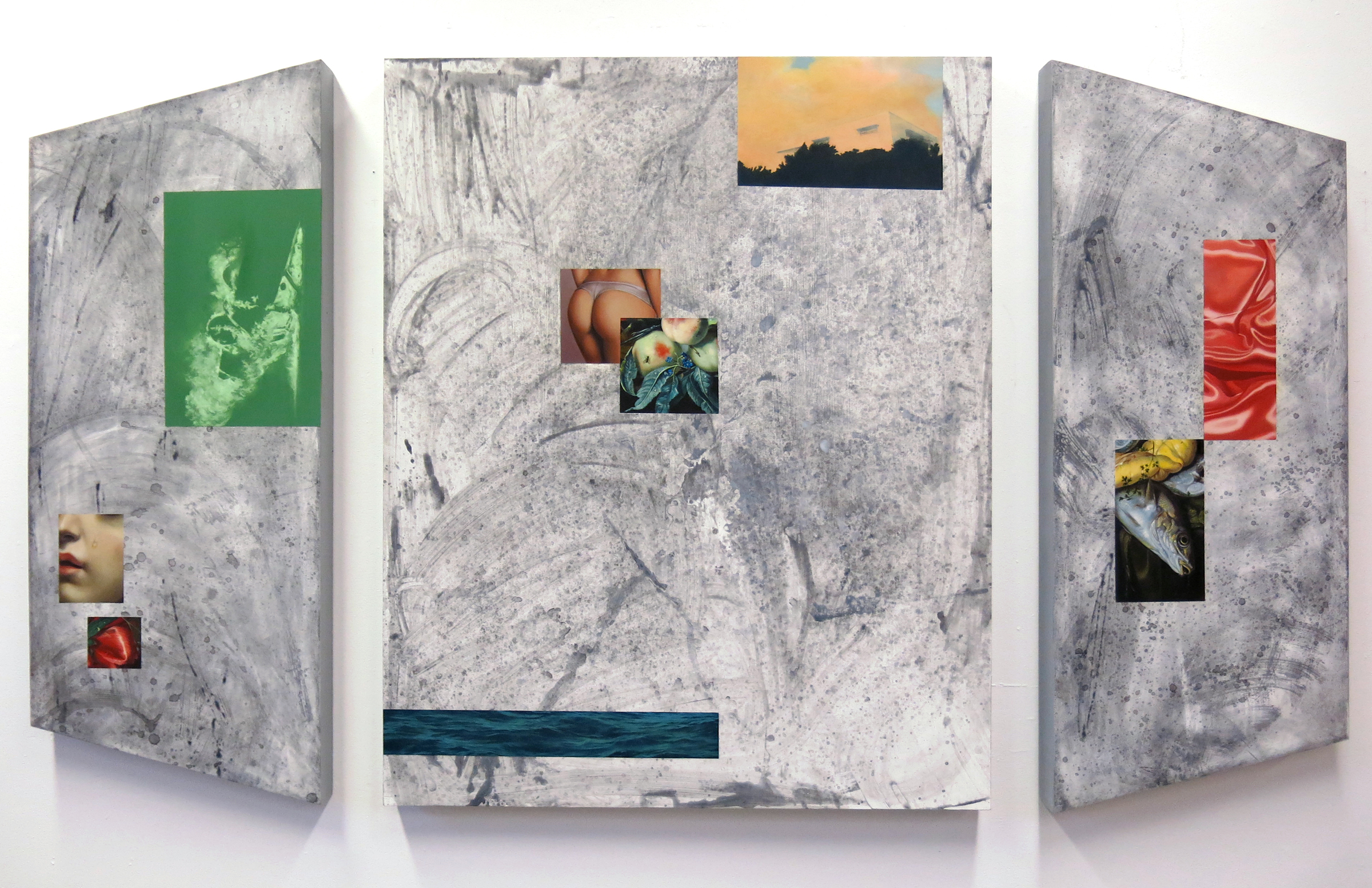

Roses Fall But Thorns Remain (Triptych), 2021,

Oil, acrylic, and ink on panel, 50 x 88 in.

Weather as a Force Multiplier, 2020, Oil, acrylic,

and ink on panel, 32 x 9.5 in.

Meredith Sellers

Pennsylvania

Most recently, I have been exploring symbols of memento mori in historical Dutch Golden Age painting. Though now considered a trope, these depictions of death flourished in Flemish painting in the 16th and 17th centuries and could be as overt as a skull accompanied by an extinguished candle or as subtle as a single ant traversing a lush flower petal, a symbol of the body’s corruptibility. Such still lives utilized goods as seemingly anodyne signifiers of wealth, power, and godliness, with frequent underlying moral messages.

- Excerpt from artist statement

Click works to the left (on desktop) or below (on mobile) to view full-screen.

meredithsellers.com︎ @mmerde___︎

Inquire︎

What first interested you in the idea of windows? Is this a theme you’ve been working with for a while?

The window has been a constant in my work for many years. My paintings and drawings explored architectural space more broadly as an undergraduate art student, but in the past several years I’ve been interested in the Quattrocento concept of the space inside a painting being so illusionistically rendered that it becomes a window of sorts. I like the idea of each painting being a “window” or portal into another space. Of course, we constantly interact with other “windows” as we navigate through digital space, and many of the arrangements of the images in my paintings reference banner ads, pop-ups, and embedded images.

As a phenomenological space, the window allows us to look out into the world, yet simultaneously acts as a barrier, isolating us from it. I would argue that the digital window operates in the same manner, so the windows in my works become metaphors for engagement and apathy—the sense of constant awareness of news and events, and a simultaneous helplessness to do anything about it; the feeling of seeing so much suffering in the world while you scroll on your device from a comfortable space, and the disconnect that represents.

Can you elaborate on your recent interest in memento mori, especially in the context of 16th and 17th century Flemish painting?

I work at the Mütter Museum, a medical history museum in Philadelphia, and my interest in memento mori was actually sparked when I taught a drawing class there featuring objects from the collection with memento mori still life props. I was fascinated when I started researching the complex symbologies of Dutch still lifes and found arcane hidden meanings, such as a bowl of cherries representing the souls of men, or an ant crawling across a flower petal symbolizing bodily corruption, and how everyday people would have been able to decode and understand the messages contained in these works.

In reading more about the luxury objects inhabiting these Golden Age still lifes, I was thinking a lot about how they also symbolize the seeds of a globalized capitalist system, built on colonialist exploitation, violence, and theft. That, to me, was another kind of death: the slow but steady, ever-increasing leeching of earth’s life-sustaining natural resources. So I was interested in the irony inherent within these works, as moralist warnings of inevitable death, and also as representations of a system that itself reaps death and destruction.

Memento mori also holds personal meaning for me. My father died when I was 14 and I think my work consequently always deals with some element of loss. When I embarked on this series a few years ago, it came after a series of deaths that included another family member, a friend, several social aquaintances, and a deeply beloved pet. It felt like death was really omnipresent in my life, just hanging around the corner. It was an eerie time and making this work was a way for me to process it that felt productive.

Is there a particular process or means of sourcing imagery that appears in your paintings?

My practice revolves around appropriation; I love the process of finding images out in the world that resonate with me. Sometimes I’m searching for images that fit an idea of what I’m thinking about, sometimes images find me and just stick. I compulsively collect and save images, filing them away into categorical folders. They come from news articles, archives, art history, google searches, targeted advertisements, and social media. Anywhere, really, that I see something that strikes me. In the digital space, all images are equal.

People sometimes assume that a practice based in appropriation is inherently cynical, that it means the artist believes there are no new images worth making in the world. Though I’m pretty cynical in other ways, I don’t see appropriation in those terms. I believe that images gain a kind of power through existing out in the world and being used in other ways for entirely different purposes. I like that people may have encountered some of the images I use while they’re scrolling online, or shopping, or flipping though a historical text. These images acquire other contexts, which have the potential to inform the work in ways extending beyond an individual’s limited view.

There is also something that feels a little magical about the found image. Collecting disparate images, placing them together, swapping out, trying something else, and then it just clicks—this set of images belongs together, it makes some kind of visual sense, has a playfulness in the interaction, reveals something that one image alone can’t. It feels a bit like when a song that’s been stuck in your head comes on the radio. A little magical.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

I borrow frequently from art historical images, and I’m interested in the systems of wealth and power that underpin Western art history and made iconographic works possible. There is no purity in art, in the Western world it has always been part and parcel of systems of exploitation and inequality. That said, there is a real pleasure in the copy for me. You can learn so much from backtracking another artist’s movements, colors, strokes. I feel like it forces me to always be learning. It’s a constant challenge to myself, which I love.