Wheeee!, 2021, Lithograph, 11 x 14 in.

La Danse, 2021, Lithograph, 15 x 21 in.

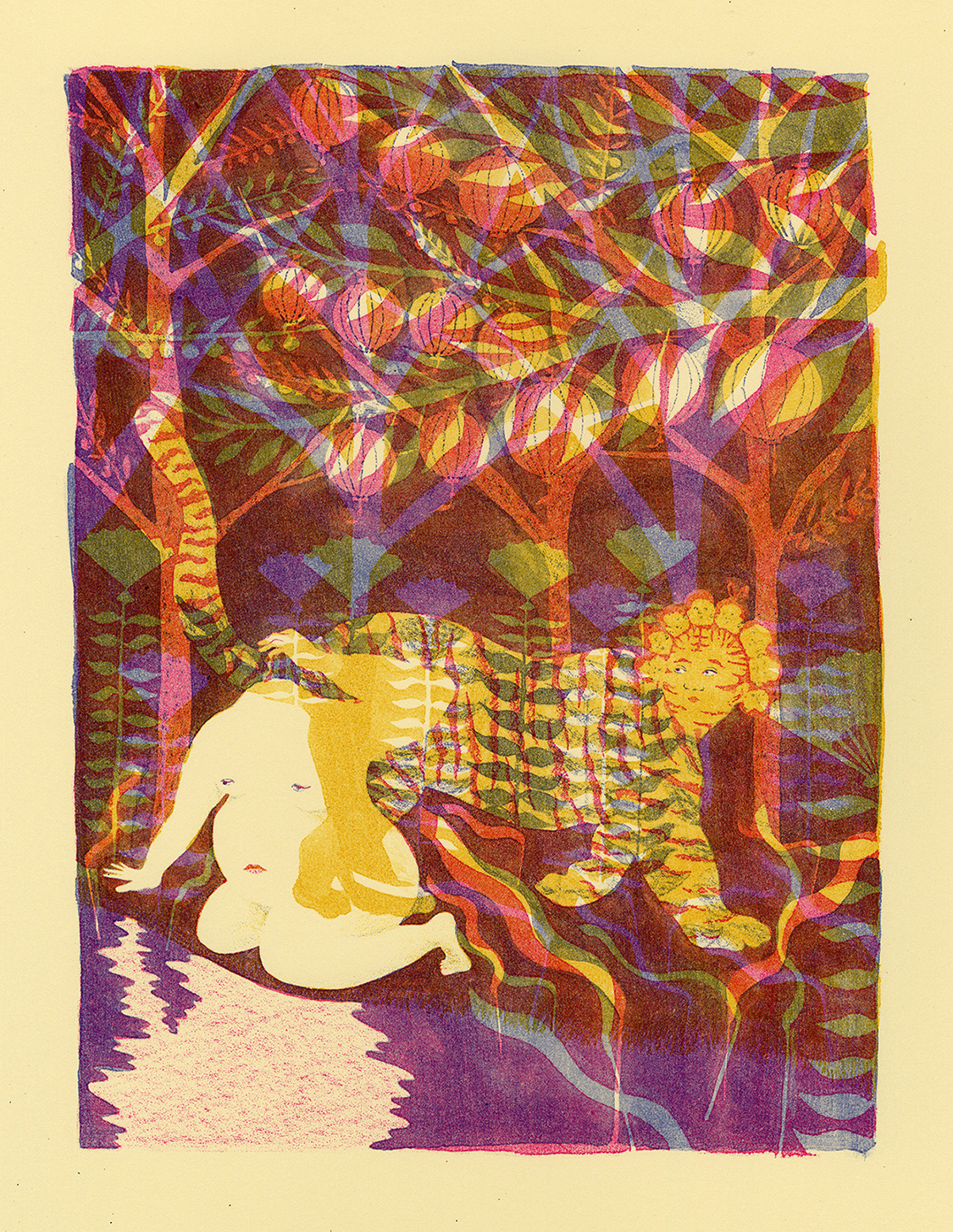

The Great Splash, 2021, Lithograph, 15 x 19 in.

Head in the Clouds, 2021, Lithograph, 11 x 14 in.

No Daffodils Grow Here, 2021, Lithograph, 11 x 14 in.

Junli Song

Arkansas

My work is inspired by the ancient Chinese cosmography, Shanhaijing, which I reinterpret through a feminist, diasporic lens. Centring around a female re-imagining of the mythological headless deity, Xingtian, as a symbol of resistance, the world created within these images exists as an imaginary realm where the liminal becomes a space of alternative existence. As a Chinese-American woman, I have undertaken the project of world-building as a way to create a space where I belong, and to make sense of the complex, often contradictory, realities of existing between cultures. Drawing upon the fantasy and humour inherent in self-making within diasporic societies, my work reveals the fluid nature of identity as inherited stories and traditions continually evolve.

- Artist statement

Click works to the left (on desktop) or below (on mobile) to view full-screen.

artsofsong.com︎ @artsofsong︎

Inquire︎

What first interested you in the ancient Chinese cosmographical text, Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas)? What inspired the female reinterpretation of the headless deity Xingtian?

I discovered the Shanhaijing while researching Chinese mythology, and I was immediately entranced by the strange deities and creatures described within it. I was particularly drawn to the character of the headless deity, Xingtian, whose head is cut off by the supreme god Di. Rather than succumbing to death, he metamorphoses: his nipples turn into eyes, and his navel becomes a mouth. This alternative form of existence in response to trauma resonated with the transnational feminist theory I was reading at the time, so I decided to create a female Xingtian as a symbol of feminist resistance. My Nu Xingtian is an embodiment of the idea that spaces of marginalisation are not merely oppressive, but also foster creativity and contestation.

How does geography or a sense of place influence your interpretation of what it means to belong somewhere?

As a Chinese-American woman, I have undertaken the project of world-building as a way to create a place where I belong, and to make sense of the complex, often contradictory, realities of existing between cultures. Drawing upon the fantasy and humour inherent in self-making within diasporic societies, my work reveals the fluid nature of identity as inherited stories and traditions continually evolve. The world created within my work exists as an imaginary realm where the liminal becomes a space of alternative existence.

What interests you in the lithographic process for these works?

I love lithography for its ability to capture an immense range of mark-making possibilities, subtle tonal ranges, and the translucency of lithographic inks, which creates beautiful overlays of colour. The way this process captures the tactile qualities of my hand painted and drawn imagery feels particularly important in these works because they describe a world that is born from my imagination.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

I am interested in the ways we perceive the world around us, both physically and conceptually. In an artist talk, Torkwase Dyson referred to perspective as ‘a Western construction of visualizing space.’ This ‘Western construction’ operates as a tool of domination by dismissing other modes of perception as being inaccurate or untrue. Yet by the same token, can alternative ways of visualizing space be transformed into pathways for liberation? In my work, I employ flatness and negative space as strategies of spatial contestation. I see flatness as an Eastern artistic convention which counters the Western use of perspective. I am also drawn to the way negative space functions as an opening, a threshold to cross over and enter other layers of the image. These moments of transformation, when absence becomes embodied, reflect how in-betweenness can be expansive, rather than limiting.